“Typewriters are too good for people. They last too long. They work too well. If they were a lot more trouble than they are, typists would be more interested in them.”

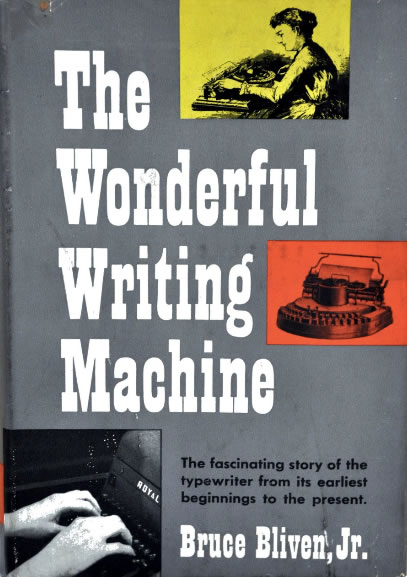

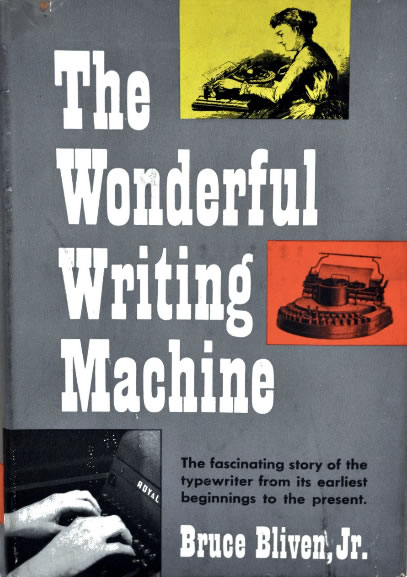

The Wonderful Writing Machine

The Wonderful Writing Machine

Bruce Bliven, Jr.

Random House (1954)

236 pages

While The Wonderful Writing Machine is not Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, the characters Bliven brings to life are every bit as interesting as Caractacus Potts, the eccentric inventor of the magical flying car. And like a good storyteller, Bliven focuses on these characters rather than the machines.

That tinkerer from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Christopher Latham Sholes, is often thought of as one of the first inventors of the typewriter. But according to Bliven he was the, “fifty-second man to invent the typewriter.” The first to do so was an English engineer, Henry Mill, who never actually made a machine, but Queen Anne granted him a patent in 1714 for his idea of, “an artificial machine or method for the impressing or transcribing of letters singly or progressively one after the other, as in writing…”

Sholes was not even the first American typewriter inventor, for that Bliven anoints William Austin Burt of Mount Vernon, Michigan who had his idea patented in 1829. It’s in this chapter, Burt’s Necessity, that Bliven brings the inventor character to life. Like many inventions, William Burt’s idea originated from a desire to save time. Handwriting was slow and tedious, and bad boy Burt was behind in his paperwork, so he closed himself in his workshop and built a box-like thing he dubbed a “typographer.” It didn’t resemble what we normally think of as a typewriter with keys, but used a dial to select a character, then a lever was pressed to make it print. This type of machine has become known as an “index typewriter.” In the end, the typographer wasn’t much faster than handwriting and never went anywhere, but it did spur others to follow.

Maker’s clubs are the rage these days and it was no different in 1867 when “Sholes and half a dozen friends spent their spare time inventing things…and their unofficial headquarters was a professional, bona fide machine shop…in a small frame building on the north edge of Milwaukee.” After the gang got in heated discussion about a writing machine, Sholes made it his mission to make one. In three months he had a working model and gathered the gang at the shop to celebrate and unveil his machine. Bliven reports that “with his eye cocked toward posterity, (Sholes) wrote: “C. LATHAM SHOLES, SEPT. 1867.” It was in all caps, as the machine had no lower-case. It’s these historical recreations that makes The Wonderful Writing Machine so much fun to read.

Like many inventions, it was not the inventor who reaped the fortunes, but the marketing and money men. While Sholes seemed satisfied with his early models, it was the promoter James Densmore who pushed for improvements. Whenever Sholes thought he’d perfected his machine, Densmore would reject it and ask for something better and more reliable. They called it the Type-Writer. But it still lived in obscurity, despite Densmore’s best promotional efforts. Eventually, the dispirited shareholders, including Sholes, sold their rights to the machine. Densmore added more marketing firepower to his team with a fellow named George Washington Yost. The two smooth talking men brought it to Washington, hoping to reap a big government contract, but came up empty handed. They finally talked their way into a meeting with Philo Remington, the eldest son of Eliphalet Remington and president of the family business of guns, sewing machines and farm equipment. Remington was sold on the idea and a big contract was signed on March 1, 1873. They had the manufacturing capability and the skilled mechanics who could transition the machine to production mode.

The Wonderful Writing Machine finally became a mass market reality under the Remington name.

This is where the book picks up speed. In the chapter, Salesmen and Thieves, we learn that salesmen were not the thieves, but in fact there were actual gangs of thieves who established fake businesses to take advantage of the common practice by typewriter salesmen to leave a typewriter or two or several for evaluation. It became such a problem and typewriters had become such a hot commodity, that some detective agencies made it their speciality in recovering the stolen property. The salesmen in this chapter are a hard working lot, lugging around twenty-five pound office standard machines around Manhattan.

But the more glamorous side of the business was the L. C. Smith showroom. If you think the Apple Store is the pinnacle of high-end gadget panache, the Smith showroom at 311 Broadway had walls that “were paneled with oak from the floor up to about waist height, and covered with green burlap from there to ceiling. The cabinets, desks and chairs were all oak. There were potted palms galore, and green velours curtains at the windows. There were only a couple of L.C. Smiths in sight, on the theory that it was psychologically more sound to display two than two hundred, as if the product were a rare jewel. If a customer brave enough to ask any questions showed up, he was led to a ‘demonstration area,’ a space separated from the rest of the establishment by hip-high golden oak partitions with shiny brass railings and short green curtains.” Moreover, Bliven says, that “for most visitors were not business executives at all, but merely tourists…and merely wanted to see if the newfangled writing machines were as slick as the advertisements said.”

To promote typewriters as modern marvels, speed typing contests were often held around the country. In the chapter, Race Against Time, the thoroughbreds of Underwood were trained in a dedicated facility in the art of high speed typing. And the team at Underwood, led by the crafty coach, Charles E. Smith, crushed the competition as if to prove that Underwood typewriters were the fastest on the planet. Smith, like a sporting scout, “haunted all the major secretarial schools…keeping his eyes peeled for kids who looked like potential champions.” The recruits were lured with a starting typists salary, but “instead of struggling with some dull executive’s dictation, the boy or girl got to join Smith’s glamorous squad of famous racing typists, known formally as the Underwood Speed Training Group. The squad worked hard. A huge, loft-like room…was its gymnasium, and the purr of typewriters doing one hundred words a minute and better filled the air eight hours a day, five days a week. Each typist had his own racing typewriter…and never let anybody borrow it, or thought of using another, for it was custom adjusted to suit his fingers. He carried it to matches…in a big plush-lined case with wardrobe-trunk-type latches and special protective fittings…in a way a concert violinist worries about a Stradivarius, holding the huge thing on his lap, if necessary, rather than letting it be consigned to a baggage car.”

Bliven brings us into the world of speed typing championships at Madison Square Garden. It’s exciting stuff with typewriters being unpacked, keyboard heights being brought into fine adjustment, stationery stacked in racing array, “the sitting down and getting up and wriggling around…(in their) special racing typists’ visors, long-beaked affairs covered in green cloth with their edges turned down sharply on both sides…they cut off any glare from overhead lights and…acted like blinders on a race horse.” After the bell sounded, “it is hard to imagine how fast a typists goes to net, say, 120 words per minute…A very good non-racing office stenographer may gross eighty words per minute, and she sounds fast. Championship speed was nearly twice that fast. In order to net 120, a racer actually typed at least 140, for each error meant a ten-word deduction.” And like other pro athletes, “the ideal state of mind–after so many days of tension–was a kind of slap-happy, passive calm. They were so nervous, they have said, that they didn’t realize what they were doing until after the first intermission. After an hour’s race, the floor around each typist’s chair was literally wet from perspiration…”

Perhaps due to the dominance at these speed contests, Underwood was also the dominant office standard typewriter during the early years. In fact, a technique used by Underwood salesmen on a reluctant buyer was to tell them, “‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” the Underwood salesman would say, ‘Just take your telephone book. Turn to any page. Pick any company in town. Give them a call and ask them what typewriter they’re buying. And if they don’t say ‘Underwood,’ I’ll pack up and go away and never bother you again.’” And it was true. Underwood had a fifty-percent share of the market, while all others competed for the other half. But in the chapter, Portables by Parachute, Bliven documents the rise of the personal typewriter, the portable, and how Royal saw this new market as their opportunity to take a lead over Underwood, who had not changed with the times.

Portables were nothing new, but it was George Ed Smith at Royal, a “salesman of the flamboyant school,” who recognized in the late 1920s that it was “important to introduce the junior machine with as loud a roll of drums as he could muster. The first of his tricks was color.” Smith “…realized that the major domo in each dwelling was the female,” and “thinking of the ladies, (Smith) had the new portable painted in two tones in a full line of colors, from quiet buff-and-brown to brilliant green-and-blue, a total of more than five hundred color combinations…” Furthermore, Smith purchased the latest model Ford tri-motor airplane with the justification that “there was no other means of transportation fast enough to get Royal portables to a hungry public.”

In fact, Royal established a “new network of 2,100 dealers who were to handle portables only.” And finally, in his biggest stunt to date, he used the Ford tri-motor airplane to drop portables by parachute to show “that the machine was rugged despite its bright coat of enamel.” The nation-wide tour saw “more than 11,000 typewriters come plunging down to earth…” People came by the flocks to see the spectacle, with typewriters opened by Royal ground crew, then typed on. But knowing that if the box landed on its side it stood a good chance of getting out of whack, the “ground crews…were trained to watch…any machine that hit the ground incorrectly was put aside, if possible, and the cases opened were those that had fallen flat.”

While Bliven devotes much space to the inventors and promoters, it’s the typewriter adjuster at work that is the sweetest tale. In fact, an entire chapter is devoted to Horace Stapenell of “1803 Broad Street, Hartford Connecticut,” who is, “one of the best of the most highly skilled workmen in the factory of the Royal Typewriter Company.” Bliven explains that Stapenell was a final adjuster, “the last step in typewriter manufacture before packing and shipping.” There were over 200 men working the same job. The typewriter arrived fully functional when it came to Stapenell’s station, however it was the final adjusting where a watchmaker’s precision was required before the typewriter was ready for sale. In the pages that follow, Bliven provides a glimpse into the art and craft of typewriter adjusting and the life of the man who performed this task. Horace Stapenell received three weeks off a year in the middle of summer, when he went on extended fishing trips in Canada and Maine and owned a “two-and-a-half-story house, white with green trimmings, where he lives in a bachelor apartment on the second floor. He drives a light blue 1953 Dodge to work every day.” Moreover, Stapenell admitted, “…I don’t mind the regular grind at all. I don’t know. There’s a lot of satisfaction in it.”

In the chapter, Quality Counts, we get further appreciation for the precision and craftsmanship required for typewriter manufacturing. Prior to Stapenell receiving a typewriter, there was someone called an “aligner” who made sure the type bars made contact with the platen in the correct position. The often used typed sample, “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog,” was not the what the aligner used. Instead, they typed, “Amaranath sasesusos Oronoco initiation secedes Uruguay Philadelphia.” Bliven tells us that, “…each of the seven words has a special reason for being, and taken as a group they combine to show up a poorly aligned typewriter in a flash.” To complete their job, aligners made “a correction in the shape of the type bar with one of twenty tools designed for bending, squeezing, pinching, nipping and crimping.” Moreover, the type bar is made of carbon steel which “makes the aligner’s job tough, for he spends his life bending bars that are built to resist bending…On the other hand, because typebars are tough, a perfect alignment, once achieved, stays perfect through months, at least, of the most frenetic typing.”

The Wonderful Writing Machine is just that, a wonderful and delightful read. If you’ve ever sat and marveled at your typewriter, Bliven gives you even more reason to appreciate your wonderful writing machine.

Used copies are available on Amazon.

Excellent condensation and review! I do have to admit, that one is a joy to read in one sitting.

Thanks, amigo!

However, I did leave out a juicy tidbit.

And perhaps this was due to the Cold War era this book was written.

When discussing Henry Mill, the Englishman typewriter inventor, Bliven says, “we might just as well admit that Mill was the first, and be thankful he was not a Russian.”

Good stuff. I’ve never used a Russian typewriter. Closest I got was an East German. Or rather, the German Democratic Republic, in the form of an Erika 10 and a Groma Kolibri & Conty. I call them The Defectors!